The early decades of India after Independence were difficult. It’s a too well-known story to repeat here that the British came to India with mercantile aspiration, it was the world’s richest nation and when they left in 1947, India had drained its wealth to the British Isles profusely to become one of the poorest on the planet.

The years soon after Independence were particularly bad. India was not producing enough foodgrains — a disproportionate size of fertile and cropping lands had gone to Pakistan on both western and eastern flanks — and had not enough foreign exchange reserve either to buy it in sufficient quantities to feed its population. By 1949, when the pre-Constitution and pre-election Jawaharlal Nehru government was still new to governing India, the country was in urgent need of securing foodgrains.

Soviet Russia (the USSR) was a close ally but its supplies were not enough. The US, which detested India’s non-aligned foreign policy approach, viewed India as a rival camp member — unlike today. In November 1949, Nehru visited the US to a rousing welcome.

In his talks with US President Harry Truman, Nehru referred to food shortage in India. Truman’s immediate response was positive but his administration staff sought to barter wheat for strategic gains. The US attempted to tie food aid to influence India’s foreign policy stance. As the US tried to use food aid as policy lever, India called the Truman administration “ungracious” and “stingy”.

With the Indian response exposing the dark side of the US’s policy interference in the newly independent nation, the Truman administration played down the controversy saying Nehru’s request was “vague” and that the Indian government didn’t follow it up formally.

This occasion to complete formality arose soon. By mid-1950, India’s food situation worsened, forcing the Nehru government to reach out to the US once again. Nehru’s sister Vijayalakshmi Pandit was the then ambassador to the US. She made the formal request for 2 million tons of wheat aid to Truman’s secretary of state Dean Acheson.

Politically astute Truman sent the food aid legislation to Congress, where some of the members were bound to criticise India over its non-aligned foreign policy, friendly ties with China and Russia, and its role as a peacemaker in Korea at a time that was sowing the seeds of the Cold War. Amid stiff resistance, the legislation was postponed. Nothing happened over India’s formal request at the time.

A conversation between Pandit and US Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn particularly upset the Indian leadership, wherein the American leader mockingly asked why “Hindu India” was not requesting for food from “Muslim Pakistan”, which he said had surplus wheat.

Nehru was so furious and frustrated at the American approach that he said, “We would be unworthy of the high responsibilities with which we have been charged if we bartered our country’s self-respect or freedom of action, even for something we need badly.”

However, Nehru later spoke positively about the food aid, suggesting India would prefer the wheat as a loan not as a gift. Mood changed in the US and Congress gave its nod to the India Emergency Food Aid Bill to loan India two million tons of wheat worth $190 million. In June 1951, Truman signed it into law in a public display of diplomacy. Pandit sat by his side while everyone was photographed standing.

While the 1950s were bad for India’s food security, the 1960s aggravated the problem with the country having been forced to fight two wars — including the one with China, suffering humiliation at the borders in 1962. By the end of the second war, with Pakistan in 1965, the food situation had worsened despite the euphoria of victory in military battles and the slogan of Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan (Victory to Soldiers, Victory to Farmers).

The end of the war also saw a forced generational shift in India’s leadership — Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri died in office while returning from Tashkent after signing a peace treaty with Pakistan. Indira Gandhi, Nehru’s daughter, became the prime minister in a big tussle for power within the ruling Congress party.

But in a country living in its villages, the spectre of famine loomed large in the mid-1960s. This presented the US with another opportunity to exert its influence. The 1960s were the years of American presidents Presidents John F Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Their foreign policy had increasingly become linked food aid to strategic interests, a tactic that would significantly impact US-India relations.

While the US spoke about humanitarian concerns, the use of food as a diplomatic tool became a key element in the US’s approach to India. President Kennedy referred to the global challenge of malnutrition, underlining that the US must “narrow the gap between abundance here at home and near starvation abroad”. With Kennedy laying the groundwork, Johnson formulated and crystalised a strategic approach to food aid over his two terms.

Public Law 480 (PL-480) or the Food for Peace Act of 1966 enshrined Johnson’s food for strategic diplomacy approach. This law has its own history in the US. It permitted the president to authorise the shipment of surplus commodities to “friendly” nations, either on concessional or grant terms.

Johnson viewed the Food for Peace programme as a powerful instrument to advance American interests, the US government’s

official history records this policy thrust. Johnson viewed food aid as a tool that served “diplomatic ends and bolstered US strategic interests”. He put the operation of PL-480 under the Department of State, placing it squarely within the realm of foreign policy.

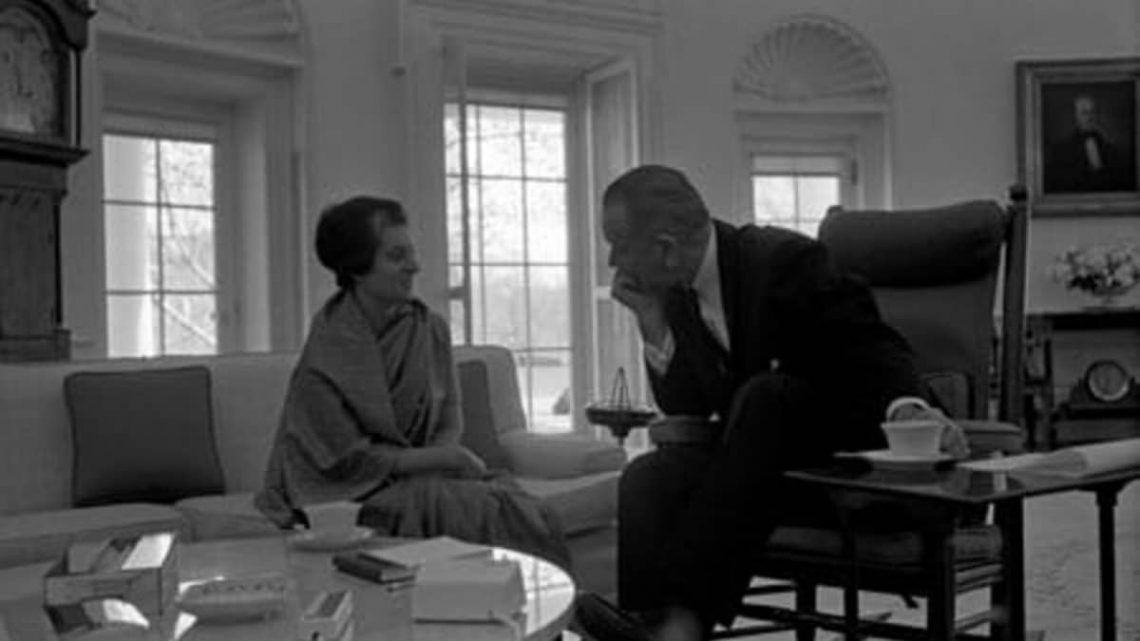

As Johnson made the US’s surplus food a tool of statecraft, using it as a bargaining chip to secure support for American foreign policy goals, the most striking example of it was India.

While India fought and won battles against Pakistan, monsoon waged another war with India with a series of failures. The result was a drastic 20 per cent fall in the national grain production — from 89.4 million tonnes in 1964–65 to 72.3 in 1965–66. Facing severe famine, India desperately needed US food aid.

Johnson got the opportunity to leverage this situation to pressure India, which had infuriated the US by criticising American bombings of Hanoi and Haiphong during the Vietnam War. He made critical famine aid to India conditional upon assurances that “the Indian government would implement agricultural reforms and, crucially, temper [its] criticism of US policy regarding Vietnam”.

The Indian mildly protested saying its position was not different from what the United Nations and the Pope had said on the bombings by the US in Vietnam, Johnson reportedly said, “The Pope and the [UN] Secretary-General do not need our wheat.”

Johnson’s retort evoked strong and emotive reactions in India, with many pressuring Indira Gandhi to say “no” to the US wheat. But the then prime minister didn’t voice her angst in public. Senior journalist of the time Inder Malhotra later quoted Indira Gandhi as telling some confidants, “If food imports stop, these ladies and gentlemen [those calling for refusing American food aid] won’t suffer. Only the poor would starve.”

However, this blatant use of food as a political and geostrategic weapon by the US showed the lengths to which the Johnson administration was willing to go to achieve its foreign policy objectives. India clearly was at the receiving end. But thankfully, this also triggered what is called the green revolution in India, making the country self-sufficient in food production as an immediate response and an exporter of grains in the longer run.

Link to article –

PL-480: When US choked food aid to shape India’s foreign policy